Who Gets to Breathe Clean Air in New Delhi?

THE NEW YORK TIMES, DEC 17, 2020

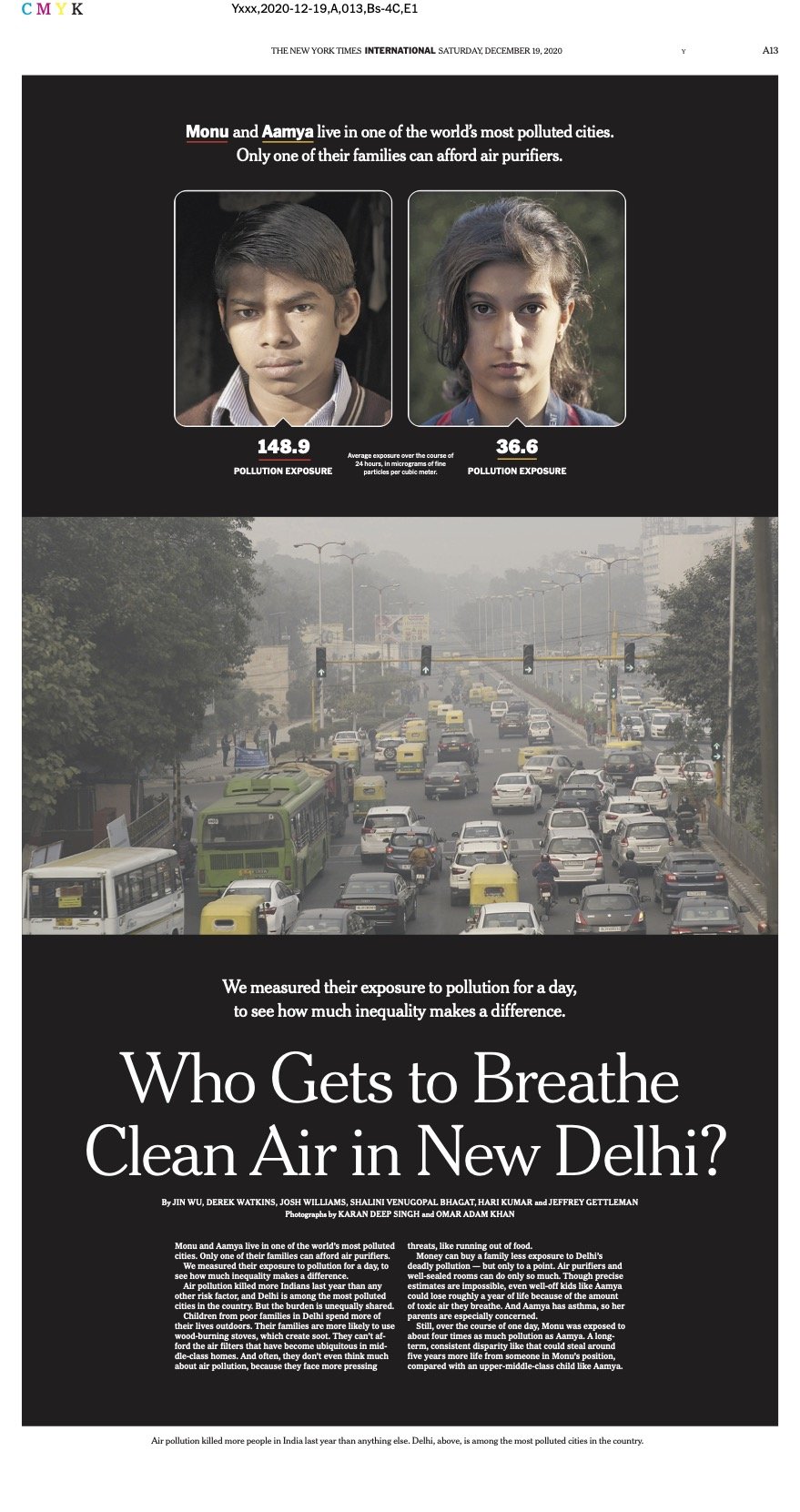

Monu and Aamya live in one of the world’s most polluted cities. Only one of their families can afford air purifiers.

Videos: Karan Deep Singh and Omar Adam Khan

We measured their exposure to pollution for a day, to see how much inequality makes a difference.

Around 7 in the morning, Monu, 13, lifts his mosquito netting and crawls out of bed onto a dirt floor. Outside, his mother cooks breakfast over an open fire.

A few miles across New Delhi, the world’s most polluted capital, 11-year-old Aamya finally gives in to her mom’s coaxing. She climbs out of bed and treads down the hall, past an air purifier that shows the pollution levels in glowing numbers.

The air is relatively clean in Aamya’s apartment in Greater Kailash II, one of Delhi’s upper-middle-class neighborhoods. Well-fitted doors and windows make the home more airtight, and its rooms purr with the sound of three purifiers that scrub dangerous particles from the air.

Monu breathes fouler air. He lives in a hut in a slum near the Yamuna River, which itself is seriously polluted. This morning, he sits in the open entryway to his house, drinking milky tea. He is the seventh of nine children and watches as one of his brothers coughs and huddles for warmth near the family’s wood-burning clay stove.

Air pollution killed more Indians last year than any other risk factor, and Delhi is among the most polluted cities in the country. But the burden is unequally shared.

Children from poor families in Delhi spend more of their lives outdoors. Their families are more likely to use wood-burning stoves, which create soot. They can’t afford the air filters that have become ubiquitous in middle-class homes. And often, they don’t even think much about air pollution, because they face more pressing threats, like running out of food.

Money can buy a family less exposure to Delhi’s deadly pollution — but only to a point. Air purifiers and well-sealed rooms can do only so much. Though precise estimates are impossible, even well-off kids like Aamya could lose roughly a year of life because of the amount of toxic air they breathe. And Aamya has asthma, so her parents are especially concerned.

Still, over the course of one day, Monu was exposed to about four times as much pollution as Aamya. A long-term, consistent disparity like that could steal around five years more life from someone in Monu’s position, compared with an upper-middle-class child like Aamya.

We know Monu was exposed to more pollution, because we measured it.

Working with researchers from ILK Labs, on Dec. 3 of last year, journalists with The New York Times tracked how much air pollution the two children were exposed to over the course of a single day.

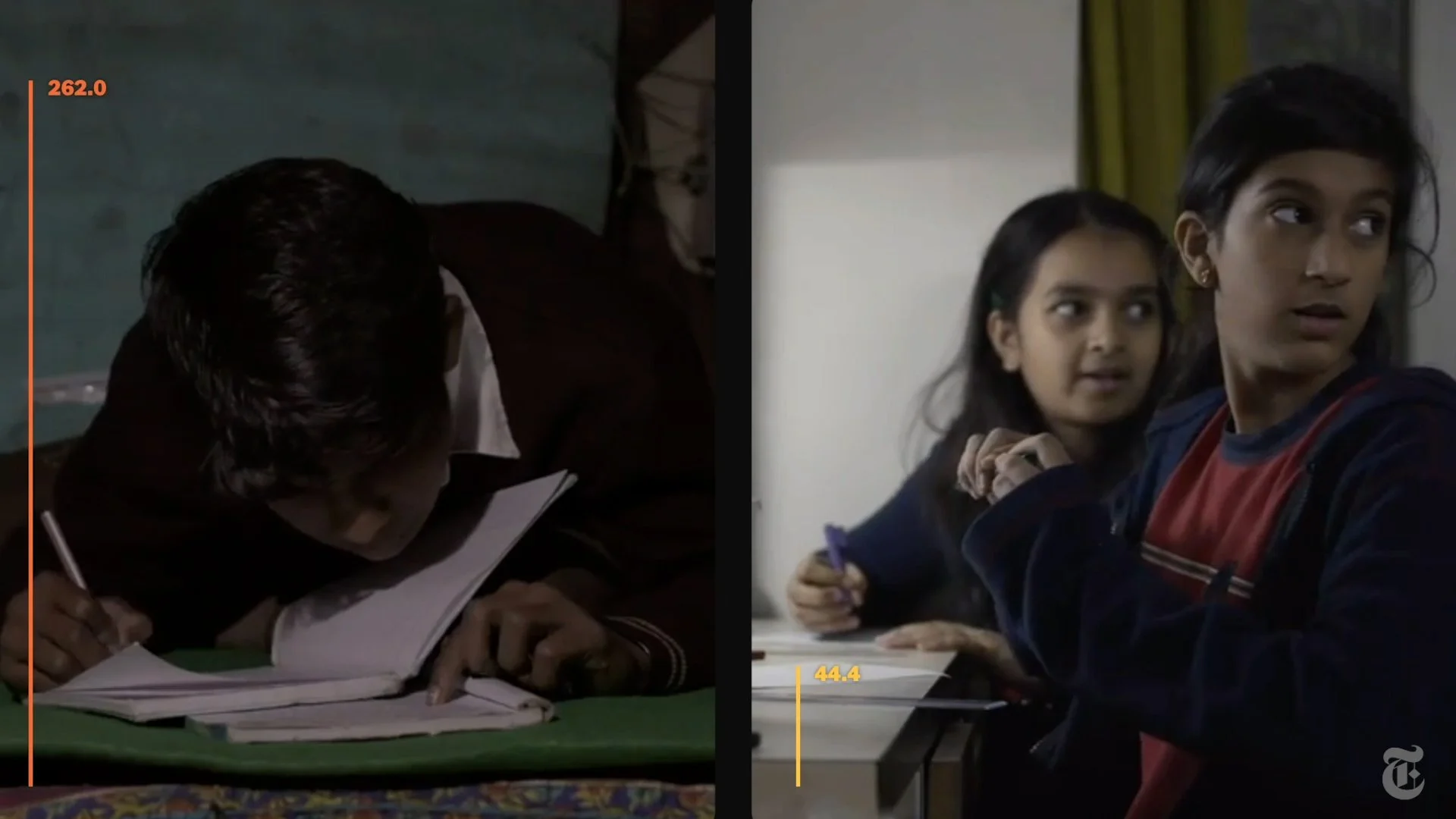

As Monu and Aamya went about an otherwise ordinary school day, we followed them with cameras and air-quality monitors that measured how much fine particulate matter was in the air they breathed at any given moment. Known as PM2.5, these are tiny toxic particles, especially dangerous because they can infiltrate the bloodstream.

Monu and Aamya have never met, but their families know about each other. Their parents agreed to participate in this report after we explained what we could learn by measuring the pollution exposure of children from different backgrounds. Aamya’s mother said she hoped it would help raise awareness about the greater health risks faced by families with fewer resources.

We could see the difference in the quality of the air they breathed, just from the filters in their pollution monitors. The differences were most pronounced early in the morning, as the children got ready for school.

Aamya and Monu started their morning commute through the smog.

Monu rode his bike to a free open-air school under a bridge, about five minutes from his house down a dusty road. He likes physical activity, and he wants to be an officer in the Indian Army when he grows up.

Aamya likes sports, too, but she wants to be a musician. She rode to school with her mom in the air-conditioned cabin of the family Hyundai.

Aamya attends a private school, the Ardee School, known for its efforts to insulate its students from air pollution. The school costs about $6,000 per year.

The Ardee School posts pollution readings on its website and on a board in the building that uses colored flags to signal the air quality. When it gets too bad, students are required to wear masks. Very few wore one while we were there, because it was not considered a bad day.

Monu’s school is free — but it has neither walls nor doors. For these students, the outside air was the inside air. Volunteer teachers struggled to be heard as metro trains thundered overhead every five minutes.

Aamya’s pollution exposure spiked the moment she stepped foot outdoors that morning. But it dropped again once she slipped through the doors of her school.

Monu, too, enjoyed cleaner air when he left behind the wood fires of his neighborhood. But at school, his levels still stayed higher than Aamya’s.

All morning, while Monu was in class, cars and motorbikes whizzed past on the street next to his school, kicking up dust and clogging the air with exhaust fumes. Aamya’s school had air purifiers in every room, linked together through a phone app that administrators monitored constantly.

Both Monu and Aamya sound fatalistic.

“It will keep increasing,” Monu says. “If we have 10 sick kids today, it’ll be 20 tomorrow. Lots of people will get sick, and their parents and doctors will say that it’s because of the pollution.”

Aamya thinks that the government is to blame, and that one person can’t make much of a dent in the problem.

“There are a lot of trees, which are not helping that much,” she says. “What my teacher says is that we can make a difference. But I don’t believe in that, because we have tried a lot.”

In the afternoon, after lunch at home, Monu went to another school, which he does every weekday. The outdoor pollution levels began to fall, as they do on most days when the morning traffic clears up and the winds shift.

There is no single cause of India’s pollution problem — and no single solution.

But Indians have learned to count on one thing: Fall and winter are pollution seasons. As air temperatures dip and wind speeds drop, pollutants concentrate over India’s cities, especially in the north, which lies in the shadow of the Himalayas. The mountain range forms a barrier that cuts down air movement even further.

The pollutants themselves come from multiple sources.

By some estimates, vehicle exhaust accounts for around 20 to 40 percent of the PM2.5 in New Delhi, which is notorious for its traffic. Household fires and industrial emissions also play a role. And as the weather cools in the fall, farmers in rural areas burn remains from their crops, sending up huge clouds of black smoke that drift for miles and settle over the city.

The end result is that the city’s smog is some of the thickest in the world.

India’s government has not made battling pollution a priority. Many officials see it as a price they are willing to pay for rapid economic growth, which has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty.

Outrage is not always easy to find on the street, either, no matter how smog-shrouded. Environmental activists say most people have no idea about how bad it really is.

“We are talking about people who grew up in rural areas and they come to the city with no preparation,” said Ravina Kohli, a member of My Right to Breathe, a nationwide clean air group. “When they see polluted air, they don’t even think it is polluted.”

There is also little data on how socioeconomic disparities may worsen pollution exposure in New Delhi, according to Pallavi Pant, a staff scientist at the Health Effects Institute. “We aren’t putting a careful enough lens on people’s occupation, or where they live, or what their socioeconomic status is,” she said.

Clearly, money helps.

Aamya’s parents, for example, have managed to shield her from some of the pollution. But it isn’t nearly enough.

In fact, researchers say, there is no amount of personal spending that can fix the problem. Much broader action needs to be taken, they say, to make India’s cities healthy for everybody — rich or poor.

At day’s end, an invisible enemy seeps through the doors and windows of rich and poor alike.

With school over, Aamya and Monu are back at their houses, settled in to do their homework.

EXPLORE THE FULL STORY WITH DATA AND MORE VIDEOS.

By Jin Wu, Derek Watkins, Josh Williams, Shalini Venugopal Bhagat, Hari Kumar and Jeffrey Gettleman

Cinematography by Karan Deep Singh and Omar Adam Khan

Field production by Sidrah Fatma Ahmed

Meenakshi Kushwaha and Adithi Upadhya from ILK Labs helped collect and analyze data

Produced by Rumsey Taylor, Leslye Davis and Josh Keller

Published on Page 1, A14 and A15, Dec 19, 2020, New York edition of The New York Times